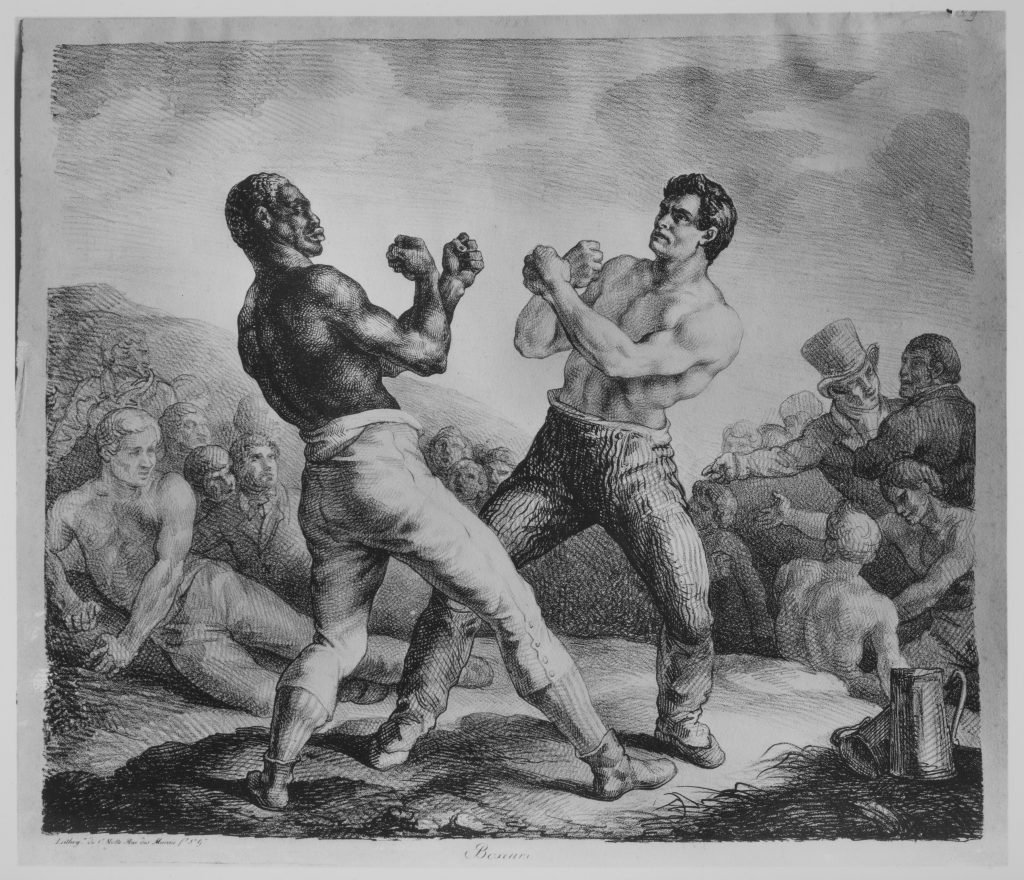

Some time in the winter of 1809, a friendless unknown named Tom Molineaux showed up in London telling anyone who would listen that he was the “champion of America” come to fight for England’s heavyweight title. This got a lot of laughs.

Molineaux was a stocky, muscular Black man who claimed to have been born a slave, possibly in Virginia, before earning his freedom in a series of no-holds-barred prizefights that enriched his owner to the point of overwhelming gratitude. He also claimed to have made his way to New York City, where he continued to make a living with his fists, before stowing away on a ship bound for England, the epicenter of professional pugilism at the time.

It’s hard to know how much of that is true. Boxing historians have questioned everything from the details of his Atlantic passage (more likely a crew member than a successfully hidden stowaway for the length of the journey, some say) to his release from bondage (would an early 19th-century slave-owner willingly part with a slave who continually won him money?), but like any good self-marketer in the fight game, Molineaux was never shy about mythologizing his own past. His eventual backers in the English prizefighting scene may have also seen the value in playing up his mysterious origins, and thus the story was born.

What most agree on, however, is that he appeared in London that winter as a raw, unschooled talent with an impressive physique, an abundance of ambition, and not much else. When he told people he’d come to fight Tom Cribb, the heavyweight champion of all England (which effectively made him the heavyweight champion of the world at the time), few took him seriously. If he wanted to break into the fight game of the London Prize Ring, they said, he should go see Bill Richmond.

In other words, the one Black fighter should seek out the other, since no one else would want anything to do with him.

The arc of the fighter-coach relationship that developed between the two men would be familiar to any modern fight fan. We’ve seen it so many times by now it’s become a tired cliche. A grizzled vet takes on a prospect who no one else seems to want. He puts some polish on his rough exterior, even when it’s a thankless task. The new kid learns fast and rises quickly through the ranks. Success goes immediately and irrevocably to his head, until soon no one can tell him a damn thing. Once the frustrated teacher can no longer control his pupil, he settles for exploiting him financially instead. It all ends in fiery human wreckage, as the fight game chews up and spits out another victim.

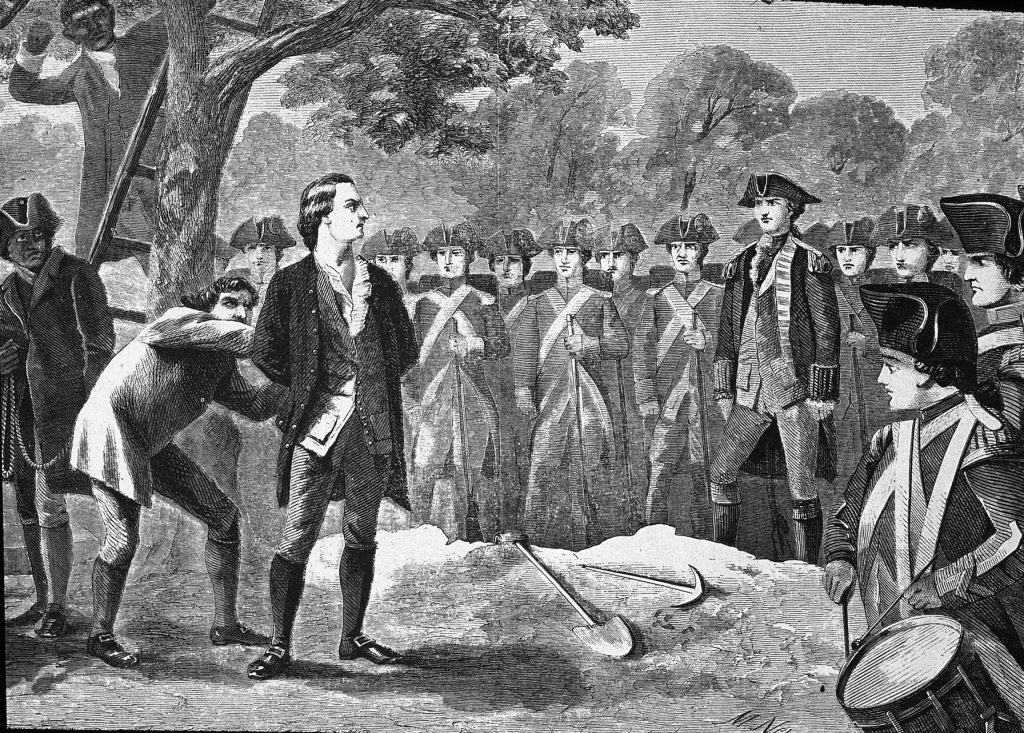

The saga of Molineaux feels archetypal now, but at the time it was novel. Then again, so was the very concept of a professional fighter. Prizefighting as we know it truly began with the bare-knuckle bouts of the London Prize Ring. They weren’t the first boxers – the Greeks were trading bare fists thousands of years earlier and the Romans even got the bright idea to add leather gloves, studded with metal to inflict maximum damage – but the Brits were among the first to maintain an active professional fight scene comparable to our own modern sport.

They had a consistent rule set, even a version of their own athletic commission to settle disputes, enforce rules, and make sure debts were paid. They had fans, often called “The Fancy,” who represented an uncommon mix of social classes for England in the time period. They even had media, like the early fight game chronicler Pierce Egan.

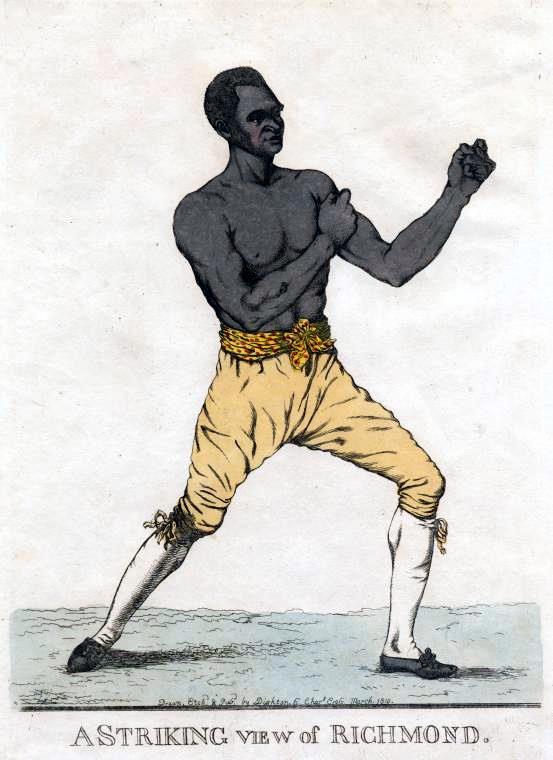

Richmond is generally regarded as the first Black fighter to break into this nascent sports scene. Born a slave in colonial America, he spent his early years in New York, in bondage to a wealthy loyalist there. It was his natural fighting ability that first caught the eye of Hugh Percy, the British general in command of New York at the onset of America’s war of independence in 1776.

In his excellent history, “Black Genesis: The History of the Black Prizefighter 1760-1870,” Kevin R. Smith relates Percy’s own recollections of first encountering Richmond, who was then just an 11-year-old boy:

“A young Blackamore was ostling the officers’ mounts, and fetching water to the horses, when a corporal of the Brunswicke division chaffed the black boy and he did make sport of the ostler’s colour. Two more Hessians joined in the folly, and one of them tripping the black boy a-purpose so that he dropped his water-can, spilling the lot. The stable-boy fetched his right hand sidelong to the corporal’s great beak of a nose, then he layed into the other two Hessians with both fists set flailing. The three men were taller than the Blackamoor boy, and their arms more prodigious of reach. Still he easily payed them in full for their merriment, and laced his right fist again and once more into their ears and shoulders, his left arm parrying and blocking their efforts to hit him in turn until at last, two of the Hessian rogues gave flight and ran, as the Brunswicke corporal fell to bleeding hard by the horse-trough. The Blackamore warrior triumphant, he fetched his water-can and went again to his work as if nought had occurred.”

The story goes that General Percy so enjoyed watching Richmond beat up grown men that he arranged fights between the boy and adult redcoat soldiers for the entertainment of his guests. Percy soon took possession of Richmond, either by buying him from his owner or just seizing him as the King’s property to help in the war effort, and afterwards Richmond became his servant. The young Richmond is even said to have participated in the hanging of Nathan Hale, a famous American spy. In several depictions of that event you can clearly make out a young man of dark complexion readying Hale for execution.

Percy brought Richmond back to England with him in 1778. Though Richmond probably didn’t have much choice in the matter, the relocation across the Atlantic gave him a better life than the one he likely would have lived if he’d remained a slave in America after the war. Percy enrolled him in a school in York, and afterwards Richmond became an apprentice to a cabinetmaker, a field he is said to have excelled in.

But even though life was better for a young Black man in England than it was in America at the time, it still wasn’t easy. All throughout his life, even after he was a famous fighter who’d befriended Lord Byron and put on a boxing exhibition at the behest of King George, Richmond faced all manner of racism, ranging from casual to at times aggressively violent. He had a reputation for levelheadedness, which mostly meant a willingness to absorb the racist taunts without flying into a rage, but he was also known to challenge his tormentors to settle things with a fight – provided they could do so as gentlemen, at the appropriate place and time.

This is how he found his way into the fight game while working as a personal valet to Lord Camelford, a famous ex-Navy captain. Camelford was a “sporting man” who loved to attend horse races and dog fights while dressed in the finest fashions of the time. He insisted that his valet also be decked out in eye-catching clothing while accompanying him, which made it even harder for Richmond to blend in with the crowd.

One day at the horse races, according to Smith, a local bully named Dockey Moore zeroed in on Richmond, berating him for his skin color and his clothes. When Richmond answered back, Moore challenged the much smaller Richmond to a fight, which Richmond gladly accepted. Away they went to find a flat piece of ground, and a half-hour later Richmond had beaten Moore into bloody submission. But Moore was a soldier, and his friends weren’t going to let it go that easily. The next time he showed up to the races, Richmond faced challenges from two members of the Inniskillings Dragoons. So he beat both of them up too.

You can see how a man might get a reputation this way, and so it was only a matter of time until Richmond ended up fighting for money. The trouble was his size. Richmond was not a big man, usually weighing no more than 150 pounds, and his first go with a much larger professional named George Maddox was a total mismatch that resulted in a one-sided beating. Richmond didn’t fight again for almost a year. But in that time, he studied the fight game intensely and eventually developed his own style to negate the size disadvantage.

“At some point he realized that his speed and agility were his best assets and that they could be used in a manner to offset a stronger or larger man,” Smith writes. “He was also a true believer in the benefits of a good defense. Thus, Richmond developed a ‘strike and duck’ or a ‘hit and get away’ style that was quite revolutionary for its time.”

Richmond would go on to have great success in the London Prize Ring, eventually earning the nickname “The Black Terror.” His most notable bout came in 1805, when, despite being in his early forties, he challenged the young up-and-comer Tom Cribb, who was a couple decades younger and, depending on the source, anywhere from 20 to 50 pounds heavier than Richmond. But instead of being just another brutish slugger, Cribb actually had some technique. He became known for his ability to “mill on the retreat” – basically a counterpunching style that allowed him to fight going backwards while still prioritizing defense to minimize the damage he took.

Cribb defeated Richmond after 90 minutes of fighting, though the fight itself might have been more stalemate than fierce combat. It effectively ended Richmond’s career in the ring, apart from a few carefully selected one-off returns, while vaulting Cribb to a heavyweight title fight against the great Jem Belcher, who he dispatched in a little over a half-hour.

Richmond retired from the ring after the loss to Cribb, but maintained a connection to the fight game in two ways. One was by training and cornering other fighters, leveraging his reputation as a “scientific” boxer to rebrand himself as a coach to pros and amateur enthusiasts alike. The other was by leaning into the classic second act of pro fighters at the time – opening a pub.

Richmond ran The Horse and Dolphin on Saint Martin Street, right near the famous Fives Court, a noted rallying point for London’s sporting crowd. It put him directly in the center of London’s pugilistic scene, and was a generally successful business venture for him. It was here Molineaux was directed once he circulated word of his plan to fight Cribb for the heavyweight crown. This might have been partially because of Richmond’s reputation as a trainer and teacher of technical boxing, but it was also pure racism. Who was going to train one Black man from America if not the other Black man from America?

Most accounts agree that Molineaux wasn’t an actual boxer when he arrived on English shores. Prizefighting as the British knew it hadn’t yet firmly taken root in America. The bouts that Molineaux participated in were much more likely no-holds-barred brawls in the “rough and tumble” style. Particularly when he was matched against other slaves, they might have often been fatal encounters.

But the London Prize Ring had specific rules, even if the sport of prizefighting itself was technically outlawed by then. There was no biting, kicking, scratching, or headbutting allowed. Rounds ended only when one fighter hit the ground, either from a punch or a throw, but to go down without cause was considered a potentially disqualifying foul. Breaks between rounds typically lasted 30 seconds, after which point the referee would call time and fighters had to “come to scratch” – stepping up to a line in the dirt to mark their readiness to begin the next round – or else be counted out. A fighter could be knocked cold at the end of one round, but if his seconds managed to wake him up in time to answer when time was called for the next round, he could continue.

Molineaux knew nothing of these rules or of the finer points of boxing as it existed at the time. But he was a physical specimen, standing about 5’8” and weighing around 200 pounds of chiseled muscle. Just the sight of him stripping off his shirt before a bout was said to sway betting odds. He also had an excellent teacher in Richmond and he learned quickly, even if Richmond had to undo some bad habits, like his tendency to throw his right hand with a kind of hammerfist style.

It’s unclear whether Richmond thought of Molineaux as a genuine prospect or simply a novelty good for generating some interest and a quick buck, but he soon matched him against a novice fighter trained by his old rival Cribb. Molineaux dropped the man early and often, but took more than an hour to finally put him away. By then, Pierce Egan wrote, Molineaux had beaten the man so badly that “it was impossible to distinguish a single feature in his face.”

The English fight crowd was intrigued right away. Molineaux looked the part, and he could fight, but he also had personality. He was often described as loud and outgoing, even arrogant He liked to drink and he loved women, many of whom loved him right back as they announced their intention to “try the black.” With his love of attention and his eye-catching physique, he became a famous local fighter in a very short period of time.

While the fighting at the time was done by people lower down on the socioeconomic ladder, it was financially supported by the upper classes. Fighters typically had to find a backer or a patron to put up the stakes for their fights, and Molineaux attracted significant attention from people like Lord George Sackville, who was ready to match him up against Cribb right away.

Richmond, however, insisted that Molineaux needed more experience. Then, as now, the fight game was susceptible to instant hype, getting overly excited about a new talent based on little actual evidence.

“Mostly Tom was a curiosity: a boisterous, black American prizefighter who rather fancied himself and his accomplishments,” Smith writes. “For the most part, the Fancy regarded Molineaux as ‘spice.’ That is to say, he brought a new life and a new interest into a sport, which had recently seen some of its slower days in England. Cribb had been champion for several years and had, for all intents and purposes, cleaned up his challengers. Without a worthy challenger for the champion, the game had fallen into a small decline.”

Many looked at Molineaux as the cure for that ailment, and Molineaux was more than happy to stoke that fire.

He continued to refine his craft under Richmond, improving both his punching technique and his footwork. In August of 1810, just about a month after his first win on English soil, he fought and defeated a well-known boxer and sailor named Tom Blake, known in the fight game as “Tom Tough.” This time an even bigger crowd showed up to watch, and Molineaux eventually knocked Blake out cold with a right hand. More than the victory itself, he had clearly improved enough to convince those who mattered in the fight scene that a worthy challenger for Cribb had been found at last.

The two would meet for the first time later that same year, just about five months after Molineaux’s debut bout. But by then, the curiosity surrounding Molineaux had turned to anxiety. It was fun having him around as a loud, brash American who fought a couple of also-rans and injected some quick entertainment into a floundering fight game. But once they truly began to consider the possibility that Molineaux might beat Cribb – that the heavyweight title of England might be held by an American, and a Black man at that – that was when “the jealousy commenced,” according to Egan.

It took a concerted effort from Molineaux and Richmond to goad the partially retired Cribb into taking the fight, and a condition of his eventual agreement was that he be given time to get in fighting shape. In later preparation efforts, he trained with an infantry captain named Robert Barclay who had risen to national fame when he walked 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours to win a bet of 1,000 guineas. Barclay was regarded as something of a fitness guru and an amateur boxing enthusiast, and he was something of a revolutionary how he trained Cribb using a regimen that consisted of sparring as well as long hikes and short runs.

The fight was set for December 18, 1810, in a field some 30 miles outside London. Right away, Richmond didn’t like the timing. Giving Cribb time to prepare after a long period of inactivity was a mistake, he thought, and fighting outdoors in the cold winter months was something Cribb was far more accustomed to than was Molineaux. Still, after such an effort to call out Cribb, the challenger couldn’t dictate terms. Molineaux and Richmond had to take it or leave it, even if it meant meeting the champion in a cold, stinging rain.

“Notwithstanding the rain came down in torrents, and the distance from London, the Fancy were not to be deterred from witnessing the mill,” Egan wrote. “And who waded through a clayey road, nearly knee-deep for five miles, with alacrity and cheerfulness, as if it had been as smooth as a bowling-green, so great was the curiosity and interest manifested upon this battle.”

Thousands turned out even in these conditions, and the fight they witnessed that day is still considered one of the greatest and most significant of the bare-knuckle era. In an article later collected in his book, “Boxiana; or Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism,” Egan provided a round-by-round summary of the fight. He repeatedly referred to Molineaux as “the moor,” and noted that betting odds started out heavily in favor of Cribb, with many betting that Molineaux wouldn’t last 30 minutes with the champion.

After Cribb threw Molineaux to the ground to end the first round, Egan wrote of the second:

“The moor rallied with a left-handed blow, which did not tell, when Cribb planted a most tremendous one over his adversary’s right eye-brow, but which not have the effect of knocking him down, he only staggered a few paces, followed up by the Champion. Desperation was now the order of the round, and the rally re-commenced with uncommon severity, in which Cribb showed the most science, although he received a dreadful blow on the mouth that made his teeth chatter again, and exhibited the first signs of claret (blood). Four to one (odds) on Cribb.”

The battle continued back and forth like this. In the fourth round, Molineaux went down off a slip on the wet, soggy ground. The fifth saw both fighters plant their feet and throw nonstop for about 30 seconds, according to Egan, which thrilled the crowd but also left them confused as to how to adjust the odds. (“The knowing ones were lost for the moment, and no bets were offered.”)

In the eighth Molineaux stood up to such punishment that Egan claimed Cribb was now feeling “somewhat mistaken in his idea’s of the Black’s capabilities.” To begin the ninth, Egan wrote: “The battle had arrived at that doubtful state, and things seemed not to prove so easy and tractable as was anticipated, that the betters were rather puzzled as to how they should proceed with success.” After Molineaux rallied to flatten Cribb with a punch that broke through his guard, Egan described the faces of those who had bet on the champion as “panic-struck.”

After this point, the picture painted by Egan’s description is less of boxing than it is of surviving. A “war of attrition,” we’d call it in the modern fight game. Both men exhausted. Both men hurt and bleeding and peering at each other through swollen slits of eyes. Both of them standing shirtless in a cold rain, trying to work up the energy to throw a punch with any force, when often enough a swing and a miss was enough to send them tumbling to the wet ground.

The next major swing happened in the nineteenth round. By this point, Egan wrote, “to distinguish the combatants by their features would have been utterly impossible, so dreadfully were both their faces beaten.” (Though, he also helpfully pointed out, looking at their faces was unnecessary since the men had different skin colors, lest we ever be allowed to forget it even for a moment.)

The crucial moment came when Molineaux battered Cribb back against the ring ropes and then trapped him there, holding Cribb and holding the ropes in such a way that Cribb “could neither make a hit or fall down” as Molineaux punished him. An argument ensued about whether this was legal or whether the referee should break them up, but while this discussion was going on most sources agree that an incensed crowd rushed the ring and pried Molineaux’s hands from the ropes, possibly breaking one of his fingers in the process. Finally Cribb went down, with Egan noting that if Molineaux hadn’t been too tired to throw punches with any real force, the blows he took in that round might have “proved fatal” to the champ.

What happened between that point and the end of the fight is still the subject of some controversy. Several sources say that in the twenty-eighth round Cribb threw a punch from too far out, missed, and was knocked out by a counter from Molineaux that left him completely incapable of making it to scratch in time for the start of the next round.

That should have given Molineaux the victory and with it the title. But according to this version of events, one of Cribb’s cornermen bought him extra time to recover by complaining to the referee that Molineaux had been using bullets secreted away in his closed fists in order to give his punches extra weight. An argument followed. Confusion ruled. An already exhausted Molineaux was left to stand there in the rain displaying his empty hands while Cribb was allowed to recover. And then the fight went on.

If true, this would be a delay tactic familiar to modern fight fans. We’ve seen corners who “accidentally” spilled water or ice on the canvas, or just conveniently forgot to remove the stool at the end of the break between rounds, all to buy their fighters more time. Several contemporary sources agree that this happened. Egan’s round-by-round account makes no mention of any of this, and instead states only: “Cribb received a leveller in consequence of his distance being incorrect.”

Is it possible Egan was so biased in favor of his fellow Englishman that he omitted this entire controversy? Absolutely. At other points in his account of the fight, he seems slow to give Molineaux credit for anything other than surprising the crowd with his ability to withstand punishment. Then again, he did note the earlier interference from the spectators, and mentioned that they’d probably injured Molineaux’s hand when prying his fingers loose from the ropes. Later, after Molineaux’s death, Egan would write that “his colour alone prevented him from becoming the hero of that fight,” so it would seem he allowed for at least some unfairness to Molineaux in the bout.

Whatever the case, the fight technically went on until the fortieth round, though Egan wrote that the thirty-fourth was “the last round that might be termed fighting.” Molineaux was fading, and after Round 39 he is said to have told his corner that he “could fight no more.” Richmond rallied him up to try another round, but Molineaux soon fell as much from total exhaustion as accumulated damage. Cribb was declared the winner. And still the champion.

The fight itself, as well as the possibility that he may have been cheated out of the title in one or more ways, was hard for Molineaux to swallow. Days after the fight a letter was published under Molineaux’s name (likely written for him since he was said to be illiterate), challenging Cribb to a rematch and noting that his “friends” thought he might have won the fight if the weather had not been “so unfavourable.”

He added: “As it is possible this letter may meet the public eye, I cannot omit the opportunity of expressing a confident hope, that the circumstances of my being of a different colour to that of a people amongst whom I have sought protection, will not in any way operate to my prejudice.”

This was an appeal more to the British sporting crowd than to Cribb. Poking at their pride in their own sense of fair play, Molineaux suggested he’d been robbed without explicitly saying it. As the modern fight game knows, the fans hate nothing more than a loser who makes excuses. And yet sometimes, especially to the loser, those excuses are nothing more than totally valid reasons.

Cribb wasn’t overly eager to do it again. He publicly accepted the challenge, but only under the condition that they fight for an increased purse of 250 guineas a side – a sum he knew Molineaux and Richmond couldn’t easily raise. Until his price could be met, Cribb would wait.

In the meantime, Richmond found other fights for Molineaux, some against much lesser fighters who had no real hope of beating him. On at least one other occasion Molineaux again faced trouble from a white crowd that couldn’t stand to see him beat a white fighter, rushing the ring and trying to tip the scales in his opponent’s favor.

Richmond never had much control over Molineaux outside the ring, but as they toured the countryside for a series of exhibitions and money fights, the relationship between them unraveled further. Molineaux had become a very famous man in England, and he wanted to enjoy it in the form of women, fancy clothes, and what passed for fast living at the time. Soon, observers began to speculate that Richmond had given up on trying to keep Molineaux reasonably sober and in something close to fighting shape, and was instead intent on wringing all the money he could out of his fighter in order to recoup his investment before it all fell apart.

Cribb and Molineaux finally met for the second and final time in September of 1811, with an even bigger crowd – some estimates pegged it at 20,000 – there to see the rematch. Cribb was even fitter and trimmer than in the first fight, having put in a full training camp with even greater focus this time. Molineaux, who may have been suffering from the early stages of tuberculosis by then, was very much the opposite. He and Richmond had been part of a touring fight troupe, earning money with shows and exhibitions right up until fight time in order to pay back the debt they’d gone into trying to raise the money for the second Cribb fight.

If the first fight was a glorious clash of titans, the rematch was more of a gross spectacle. Cribb easily battered the out of shape Molineaux, doubling him over with body punches that pounded at his now soft belly. Still, Molineaux had that same tremendous heart and punching power that he’d started with. In the fifth round, he knocked Cribb down with damaging blows that had Cribb’s supporters genuinely worried. But his condition soon betrayed him, and Cribb took over the fight.

In the ninth, Cribb knocked Molineaux out so severely that there was no hope of him making it to scratch in time to continue. The fight should have ended there, but Cribb refused to accept the victory. Maybe he wanted to make a point after the accusations that he’d been given too much to recover in the first fight. Maybe he was just angry at Molineaux for some of the things he and Richmond had been saying about the champ in an effort to entice him into a rematch. Whatever the cause, he seemed to want to punish Molineaux, and so he insisted on giving him nearly two minutes to recover.

When the bout resumed, Cribb pummeled him mercilessly, at one point breaking Molineaux’s jaw with a punch. Again Molineaux failed to come to scratch in time, and again Cribb refused to accept victory. Even though Molineaux was clearly finished, Richmond pushed his fighter out for another round. In the eleventh, Cribb knocked him completely unconscious to settle the matter for good. The whole thing took just under twenty minutes.

Richmond’s association with Molineaux dissolved right there. Some sources say he abandoned his fighter the same day, leaving him to make his own way home with a broken jaw and battered body. In a distinguished life as a fighter, trainer, and businessman, it’s one of the only critiques anyone could plausibly lodge against Richmond – but it’s a bad one.

In his historical novel, “Black Ajax,” George MacDonald Fraser depicts Richmond as thoroughly fed up with a man in whom he’d placed his own vicarious hopes. In a chapter from Richmond’s perspective, Fraser imagines his lasting animus toward Molineaux.

“He could ha’ been the Champion, the black Champion of England! He threw it clear away. I used to dream ‘bout that Championship, long ago, when I was a young miller, and thought myself a prime chicken. But I soon saw ‘twould never be, for me, and time passed – and then came Tom, and when Buck Flashman and Pad Jones showed me what was in him, oh, ten times what there ever was in me, or any other fighter I ever saw, black or white … then I dreamed again, and knew such a burning ambition as I’d never felt for myself – to see him cock o’ the Fancy, Champion of England, and pay back all those years and sneers and see their pride humbled and their insults thrown back in their teeth. … Guess you think the Championship of England ain’t worth that much hate? Mister, you don’t know the English. Guess you think I must be dicked in the nob to feel the bitterness I feel? Mister, you ain’t a nigger … and you never been a slave.”

Molineaux would go on to have several more fights of an increasingly depressing nature. He was clearly unwell, but continued on anyway, making what money he could off the lasting power of his name. In some fights he seemed to break with reality, talking to people who weren’t there and accusing opponents of fouls that never happened. Eventually he was destitute, taken in by a few Black soldiers who took pity on him in Galway, where he died on August 4, 1818.

The boxing historian Henry Downes Miles, author of “Pugilistica,” later described him as “illiterate and ostentatious, but good tempered, liberal, and generous to a fault. Fond of the gay life, fine clothes and amorous to the extreme, he deluded himself with the idea that his strength of constitution was proof against excess. He was a brave but reckless and inconsiderate man, on whose straightforwardness and integrity none who knew him ever cast a slur; nevertheless he was the worst of fools, inasmuch as he sacrificed fame, fortune and life; excusing himself by the absurd plea that he was a fool but no one but himself.”

It’s fair to say that without Molineaux and that first fight they shared, Cribb’s legend would never have grown so immense. For a time he was the country’s most famed sportsman. He also ran a pub, and one which bears his name and likeness still stands in London today. His triumphs were eventually celebrated with the presentation of a belt made of lion skin. It was probably the first championship belt ever awarded, and it helped establish the tradition that continues now, some two centuries later.

What’s strange is that, while the story of Cribb and Molineaux captivated England at the time, there was almost no mention of it in Molineaux’s home country. In America, the exploits of a Black fighter apparently weren’t considered newsworthy. Back home, the slave who’d very nearly become a champion by beating the British at their own game was still just another nobody, hardly even worth mentioning. The familiar arc of the life he’d lived, however, was doomed to be repeated again and again.

Hey, if you made it this far and didn’t hate it, you should consider signing up for the Co-Main Event Patreon. There you can comment on these posts, argue with other people about them, even call us names or whatever. You also help support the CME and keep the discourse free and unfuckingfettered.