Before he left sportswriting for life as a novelist, Paul Gallico took one last look back at the world he’d covered for the New York Daily News in his book, “Farewell To Sport,” which included this reflection on former heavyweight boxing champion Primo Carnera:

“There is probably no more scandalous, pitiful, incredible story in all the record of these last mad years than the tale of the living giant, a creature out of the legends of antiquity, who was made into a prizefighter. He was taught and trained by a wise, scheming little French boxing manager who had an Oxford University degree, and he was later acquired and developed into the heavyweight champion of the world by a group of American gangsters and mob men; then finally, when his usefulness as a meal ticket was outlived, he was discarded in the most shameful chapter in all boxing.

This unfortunate pituitary case, who might have been Angoulaffre, or Balan, or Fierabras, Gogmagog, or Gargantua himself, was a poor simple-minded peasant by the name of Primo Carnera, the first son of a stone-cutter of Sequals, Italy. He stood six feet seven inches in height, and weighed two hundred and sixty-eight pounds. He became the heavyweight champion, yet never in all his life was he ever anything more than a freak and a fourth-rater at prizefighting.”

It goes on like that for about ten more pages. And it does not get any kinder or more generous. Gallico describes Carnera as a great big fraud, a “floundering giant” with jagged teeth and gummy lips who “invariably smelled of garlic,” and who couldn’t fight even a little bit, though both he and the public were made to believe otherwise. The fights he won – and there were 88 of those, between 1928 and 1946 – were almost all fixes, according to Gallico. And he’s not the only one to have said so.

If modern fight fans know Carnera at all, this is probably how they know him. As a phony. A giant hype job. Discovered as a French circus act, conned into believing he was a fighter, brought to America like King Kong in chains and then handed over to the mob, which swindled him of nearly every penny while making him a celebrity and, at least nominally, a champion.

This somewhat simplistic version of Carnera’s story seems to have taken hold gradually, and then all at once. In 1956 it was further solidified into fact by the Humphrey Bogart film “The Harder They Fall,” based on a novel which was obviously supposed to be a retelling of Carnera’s rise and fall with a few names and details changed just enough to allow it to pass as fiction. Carnera even sued Columbia Pictures over the film, alleging irreparable damage to his reputation, but the lawsuit went nowhere and the damage took hold for good.

To what extent this narrative is true is still difficult to determine, but either way Carnera’s story stands as an example of how exploitative the fight game can be. Here was a man who was pulled into it more because of how he looked than because of what he could do. Once in that world, he made millions of dollars that he never personally saw or spent, yet the public scorn for his perceived fraudulence was laid entirely on his shoulders.

All indications are that none of this was anything Carnera had planned for his life as a young man growing up in the northeastern corner of Italy. According to Carnera’s own recollections, many of which were passed on by his children, the prevailing feeling of his childhood and his teenage years was hunger. He was always large. He never seemed to get enough to eat. He moved to France to work as a bricklayer and later a carpenter, and when he was 17 he began training at a nearby gym frequented by other Italian immigrants.

His size and natural physical power caught the attention of a traveling carnival, which offered him a job as a strongman. What Carnera wanted to know was, would he finally get enough to eat? When he was assured that he would, that seemed to be enough for him. It was an improvement on the circumstances he’d known all his life.

Part of Carnera’s strongman duties involved flexing his muscles and lifting weights, but also wrestling and fighting volunteers from the crowd. Sometimes those matches were fixes and the “volunteers” were planted in the audience, but other times they were genuine fights. One night while the carnival toured the French coast in 1928, Carnera knocked out a tough local challenger in front of a journeyman heavyweight named Paul Journee, who ran a gym in town. Journee later convinced Carnera that he could have a more lucrative career as a boxer, and soon he began training him.

It was Journee who introduced Carnera to Leon See, the “wise, scheming little French boxing manager,” and See who later brought Carnera to America and into the clutches of organized crime figures. But even here, at the very start of his boxing career, the mold was already set.

For “discovering” Carnera and passing him onto See, Journee owned a 25 percent stake in Carnera, according to a later story in The Ring magazine. See also came in for a piece of Carnera’s future earnings, though his share was later diluted by some of the unsavory Americans who gradually took over Carnera’s career while pushing See out. From the beginning, Carnera was owned and controlled by others, with very little of the money he earned actually finding its way into his hands.

Carnera was not a naturally gifted boxer. In his book, “Primo Carnera: The Life and Career of the Heavyweight Boxing Champion,” Joseph S. Page points out that after watching him spar for the first time, See initially passed on him, dismissing Carnera as too big and not at all athletic. He improved quickly with training, however, and after being called back to look at him a second time some weeks later See remarked: “That is not the same boy, that is a different person!”

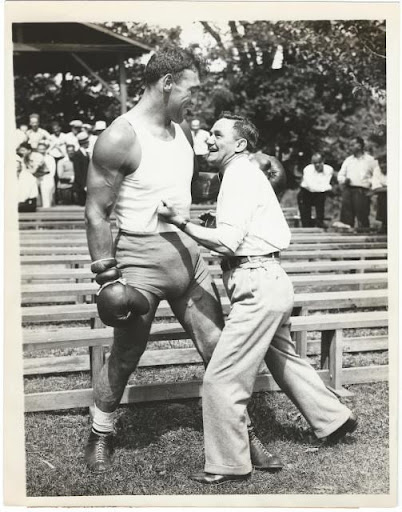

Still, Carnera’s handlers knew what they had and what the appeal was. Carnera was a physical spectacle. Usually billed somewhere around six-foot seven inches, he towered over most heavyweights of the era and wowed audiences with his muscular physique. Right away, the move was to play up his size, strength, and raw physical ability, even as he fought his way to some unimpressive early wins on the European scene.

Later, the same managers and handlers who helped launch his career would go on to claim that Carnera’s early fights were all fixed. See, who by then had long been cut out of the money and had reason to be bitter about it, claimed that Carnera’s European opponents had been paid to take dives. Walter “Good Time Charley” Friedman, who was See’s initial connection to the American market, made similar claims once he was no longer in a position to profit off Carnera.

Most of the time, the story they told insisted that Carnera had no knowledge of the fixes. He thought he was legitimately winning these fights. It was his managers and opponents who knew different.

Page’s biography is certainly written with a pro-Carnera slant, and the author explains early on his intention to dispute the notion that Carnera was never a legitimate boxer. But it also makes some fair points about these retroactive fix claims. If you look at early opponents like Feodor Nikolaeff, what you see is a boxer with a losing record, on a very long losing streak, who took a fight with Carnera and lost, just like he had done in his ten previous bouts and the five bouts that followed.

But as students of the modern fight game know, you don’t select a guy like that as an opponent if you also need to pay him an extra thousand dollars to lose. The whole reason you choose him is because of how likely he is to lose all on his own. That is very much his function as the “opponent,” in boxing terms.

There was a lot of that in Carnera’s early years, and it was all part of a plan. This plan would not be unfamiliar to fight fans of today. How do you create hype for a new prospect who generates a lot of interest but isn’t yet a seasoned fighter? You do it through careful matchmaking. Carnera’s official record shows five fights in his first year as a professional. Only one came against an opponent with a winning record. (That opponent, Epifanio Islas, was 5-3 when he met Carnera, but finished his career 10-20-7.) Many of his opponents retired soon after facing him, and sometimes even immediately after.

The managerial play with Carnera was as much about billing him as an oddity worth paying to gawk at as it was about establishing him as a legit heavyweight – and it worked.

Before he even crossed the Atlantic, Carnera was being written up in New York newspapers as a bizarre coming attraction. The month after he arrived in New York by ship at the end of 1929, the United Press ran a headline that read: “Giant Italian to Tour Country and Take Things Easy For About Six Months.” Newspapers ran stories about the eight-foot bed that was constructed to accommodate Carnera’s frame during the Atlantic crossing, or about how much he ate during the trip. All this succeeded in piquing people’s curiosity. Whether the guy could fight or not, he began to seem like a show worth seeing.

Once in America, Carnera’s career fell increasingly under the control of people who, if they weren’t straight-up gangsters, at least kept very close ties with those who were. Friedman immediately introduced See to his friends Bill Duffy and Owney Madden in New York. They met at a Manhattan speakeasy owned by Duffy, an interesting man who by this point had been to both Sing Sing and the U.S. Navy, but had found his calling as a nightclub and restaurant owner with ties to both the fight game and organized crime. He was reported to be a good friend of Jack Dempsey’s, and was sometimes rumored to be the secret manager for Dempsey and other top fighters. (Fun story about Duffy: He was once picked up by police in connection with the murder of a nightclub performer in Brooklyn. When they brought him into the station, the cops discovered Duffy had a fresh bullet wound in his shoulder that he refused to explain.)

Madden was even more notorious in New York, where he’d come up among the tough street gangs in Hell’s Kitchen. He earned the nickname “clay pigeon of the underworld” for how many times he’d been shot, though he was probably better known simply as “Owney the Killer.” After a prison stint for manslaughter, he found success as a bootlegger, eventually muscling his way into an ownership share of various nightclubs and speakeasies. He even bought the famous Club Deluxe in Harlem from former heavyweight champ Jack Johnson.

These were the people who would shape Carnera’s boxing career, and it was well-known that they’d bent a law or two in the past. They soon bought out See (though later speculation would suggest this was one of those “offers he couldn’t refuse,” in the gangland sense), and installed Carnera at Stillman’s Gym in New York. There he worked with former featherweight champion Abe Attell, who was almost as renowned as a fight trainer as he was for his alleged involvement in Arnold Rothstein’s plot to fix the 1919 World Series.

The plan for Carnera’s stay in the U.S. wasn’t exactly a secret. The United Press ran a story asserting that Carnera would be “built up into the biggest fistic attraction since Jack Dempsey’s hay-day by touring the country and fighting more or less easy opponents.” How did the writer come by this information? Straight from “the giant Italian’s crafty board of managers,” the story claims.

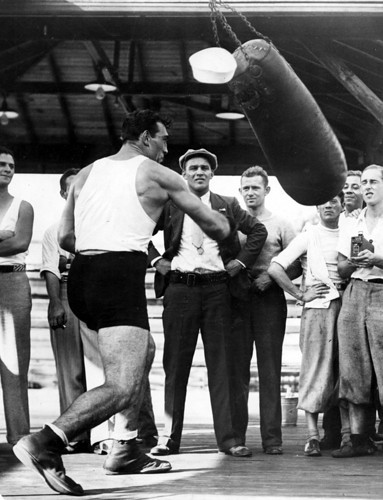

This is more or less exactly what happened throughout 1930, Carnera’s first year of competition in the U.S. He fought 26 times that year – six times in the month of March alone – and he won every fight except for a decision loss to Jim Maloney in Boston. (He’d get his revenge with a decision win over Maloney five months later.) Still, right away some of these fights drew scrutiny and suspicion.

Carnera’s first-round win over Elzear Rioux in Chicago was met by boos and chants of “fake!” from a crowd angered by Rioux’s repeated flops. The Illinois State Athletic Commission initially withheld the purses and suspended both men, but in a hearing shortly after the fight both Rioux and the referee for the bout attributed his poor performance to overwhelming fear at Carnera’s size and physique.

There was a similar incident a couple months later against former Notre Dame and Chicago Bears offensive lineman George Trafton in Kansas City. It took Carnera less than a minute to put him away, during which Trafton landed no punches and seemed to go down without being hit. The Missouri Boxing Commission suspended Trafton for what it called a “54-second swooning session,” but laid no blame on Carnera.

The most suspicious fight yet came the following month in California, when Carnera knocked down Leon Chevalier in the sixth round, only to have Chevalier’s manager throw the towel as soon as he got up. This enraged fans, who immediately called it a fake, and resulted in Carnera’s entire entourage having their licenses suspended by the California State Athletic Commission. Both Chevalier and his wife would later claim that he’d been asked to lay down in the fight, but had refused. It was also later rumored that his manager, Tim McGrath, had rubbed some foreign substance in his eyes between rounds, and only when that failed to stop his fighter did he throw in the towel.

The California commission eventually released Carnera’s purse, since it couldn’t prove he was to blame for the actions of Chevalier’s manager, but the suspensions had a ripple effect on other commissions, some of which backed up California by issuing matching suspensions of Carnera and his management team. Suddenly the plan to build up Carnera seemed to be in danger. The great sportswriter Grantland Rice later called the towel thrown by McGrath “the mostly costly piece of tapestry ever known.”

Once rumors of fixes had made the rounds, other fighters from Carnera’s past came forward to claim they’d also been paid to lose. Whether it was true or just a way of jumping on the bandwagon in an attempt to erase a loss off their records, it was hard to tell. It didn’t help that, even when Carnera’s wins didn’t appear suspicious, they came against handpicked opponents who seemed obviously hired to lose. Sportswriters opined that, while Carnera might actually be able to fight, he wasn’t getting much of a chance to prove it.

That began to change the following year, as Carnera faced legit heavyweights like Jack Sharkey, (who beat him on points before taking the heavyweight title from Max Schmeling in his next fight) and King Levinsky, a heavyweight mainstay who Carnera beat by decision.

But while Carnera’s career prospects were improving, his financial outlook was crumbling. He was dogged for years by a lawsuit and subsequent judgment in favor of a waitress in London who claimed Carnera had promised to marry her. He faced bankruptcy proceedings in New York, where his financial advisor (who was likely also helping to fleece Carnera for his mob friends) told a court that there was no point in trying to discuss money with Carnera, according to Page’s biography.

“He simply will not listen,” Luigi Soresi said. “He does not understand financial problems, and, what is worse, cares less.”

If this was true, it was perfect for Carnera’s team of handlers. In his first two and a half years of fighting in North America, it was estimated that Carnera had earned about $900,000 – roughly $19 million, in today’s money. He personally saw almost none of that money. When he eventually rematched Sharkey in 1933, this time with the heavyweight title on the line, his purse was $17,000 ($363,000 when adjusted for inflation). After his management and trainers made their deductions for “expenses,” that was whittled down to about $360 ($7,600 in 2021 dollars) that actually made it into Carnera’s pocket.

The validity of the title fight against Sharkey is still debated by boxing historians. The official record shows that, in the sixth round at the Madison Square Garden Bowl, Carnera knocked out Sharkey with an uppercut to claim the title. Sharkey would go to his grave denying that the fight had been fixed, though some would never believe him. Even Carnera’s former manager Friedman, who claimed that the early fights were fixes, insisted that his win over Sharkey was for real.

“Every once in a while Carnera could complete a perfect punch,” Friedman said. “That’s what happened when he caught Sharkey with that right uppercut in the sixth round.”

When you watch the film of the fight, it’s hard to imagine this as a clear fix. For one thing, Sharkey lands several hard blows on Carnera’s jaw, which would seem risky if the plan was for Sharkey to lose in the end. For another, while Carnera doesn’t look like the slickest technical boxer, he also doesn’t look anything close to the total fraud that some people made him out to be.

His style is built around his height and reach. Even his detractors usually gave him credit for developing a strong jab. The final uppercut that floors Sharkey doesn’t look completely devastating, but it’s also worth remembering that Carnera was about sixty pounds heavier than the champion in this fight, and stories of his almost freakish strength followed him everywhere he went. (According to one such tale, Carnera once stopped during an afternoon stroll to lift a car that had flipped onto its side, setting it upright again before continuing on his way.)

Carnera would later tell his children that he truly wasn’t sure whether his early bouts had been fixed, but he did believe the title fight was legit. In his words, it was “too important” to be a setup. Sharkey also maintained that it was on the level, even if that meant insisting that he really had been knocked out by a fighter regarded as a phony by the rest of the sport.

Carnera would defend the title twice, winning decisions against Paulino Uzcudun in Rome and Tommy Loughran in Miami, before dropping it to Max Baer in a one-sided drubbing that saw Canera dropped twelve times, including three knockdowns in the first round. In the retelling of Carnera’s career that maintains he was always a fraud, this is often held up as his first totally legitimate fight.

In Paul Gallico’s version, the Loughran fight, which Carnera won mostly by using his size and weight in the clinches, made it “obvious that he was a phony and the first stiff-punching heavyweight who was leveling would knock him out. Max Baer did it the very next summer.”

Of course, Carnera also got up eleven times after being floored by Baer, which would suggest that he was tough, if nothing else, and game for a fight. Also, to buy this total fix narrative you’d have to believe that Carnera’s mob-connected handlers successfully fixed nearly four years’ worth of fights – easily over 50 pro bouts, at least – many of which went the distance and required Carnera to get drilled and dropped and cut open just like any other fighter.

The right hands he took from Sharkey alone would seem to have put the mob’s betting proceeds in serious jeopardy. And if you believe he beat Sharkey on the level, but none of the bouts that preceded it, that would mean he was good enough to beat the champion but none of the contenders along the way, which seems farfetched.

What is clear is how Carnera was treated after he lost the title and his value to his handlers had diminished. After a few wins in South America, he returned to face a young, undefeated Joe Louis in 1935. It was the classic fight game move of feeding a former champ to a future one, all for the rub that a famous name would provide. Louis took Carnera apart with right hands, dropping him several times before the fight was stopped in the sixth. It signaled the end of Carnera’s time in the heavyweight title picture, and vaulted the future champ Louis into contention.

Carnera would fight a few more mostly inconsequential bouts. His serious attempts at a career ended in 1938, when he lost a kidney to diabetes. He was used as a fascist propaganda tool by both the Italian and the German governments before and during World War II, though Carnera himself seemed to have no real political affiliations beyond a desire to be liked.

He returned to the ring in the mid-1940s, just to earn enough money to finance a return to the U.S., where he’d been promised a job in professional wrestling. Ironically, this was to be the most lucrative chapter of his life. Wrestling promoters treated him fairly and paid him what he was owed, according to Carnera. He became a bankable attraction for them, working with wrestling greats like “Strangler” Lewis and Lou Thesz.

As his health declined, Carnera returned home to Italy, where he died of liver disease and complications from diabetes in 1967. In his final years, nothing hurt him as much or did more to solidify his reputation as a fraud than the film “The Harder They Fall.” In it, a South American giant named Toro Moreno is propped up by mob interests, aided by an unemployed sports writer played by Humphrey Bogart. Moreno has no boxing ability whatsoever, but believes himself to be a great fighter after winning a couple dozen fights that were fixed without his knowledge. The character is childlike and simple, and is eventually cut entirely out of the money by some tricky accounting work.

The film is so obviously and brazenly based on Carnera’s career that at times it feels like it’s taunting him. For instance, the character of Moreno wins his first fight after his opponent’s corner rubs a foreign substance in his eyes and then throws the towel against his wishes. He’s also involved in a fight where his opponent, brain damaged and hindered by a bad flu, dies shortly after the bout. This is a clear reference to the death of Ernie Schaaf, who died of meningitis a few days after fighting Carnera in 1933.

Perhaps most cruelly, the fighter who eventually exposes the character of Toro Moreno is played by Max Baer, the man who was said to have done the same to Carnera when he took the title from him in 1934. Baer had done a number of film roles and was a decent actor, but he was also nearly 50 when the film was made and he looks every bit of it. There would seem to be no reason to cast him as a champion in his prime except to make it more clear that the movie is really about Carnera.

Just to extend the cruelty to Baer himself, the script also requires Baer’s character to give a short speech in which he laments that Moreno got credit for killing the man who he had battered nearly to death in an earlier bout.

“I’m the guy who nailed Gus, murdered him for 15 rounds,” Baer’s character says. “Don’t know what held him up, but when Gus left the right that night he was a dead man. All your joker did was tap him. I did all the work and they gave your guy all the glory.”

In reality, Baer really did put a severe beating on Schaaf before he fought Carnera, but so did several other opponents. Baer had also been involved in another fight in which he really did kill an opponent named Frankie Campbell in the ring, and it haunted him for the rest of his life. Baer later wrote that nothing in his life could ever affect him more than the death of Campbell. His son recalled how Baer often woke up in the grips of the same nightmare, “muttering, ‘You’re okay! Please be okay!’”

Imagine, then, when Baer was asked to play a thinly disguised version of himself, beating a thinly disguised version of Carnera, and complaining that he hadn’t gotten the “glory” he deserved for killing a man in the ring.

Carnera’s $1.5 million lawsuit against Columbia Pictures alleged that his reputation had suffered irreparable harm as a result of the film. A judge dismissed the suit, explaining that a person “who becomes a celebrity waives the right to privacy and does not regain it by changing his profession from boxer to wrestler.”

Carnera seemed more hurt and confused than angry. “That’s not true,” he was quoted of saying about the film in a British newspaper. “That’s not my story. I haven’t done any harm to anybody, why do they want to punish me?”

There is one notable area where the movie veers into pure fiction. It’s at the end, when a guilt-ridden Bogart takes his share of the money and gives it to the fraudulent boxer, then puts him on a plane home to South America and out of the clutches of the mob.

In real life, no one ever did give Carnera the money he’d earned as a boxer, nor did they put themselves at risk to look out for his well-being. Even this movie, which ends with a call for the federal government to investigate corruption in boxing, ripped him off and gave him nothing in return, just like his many handlers had since the beginning of his career. But maybe Carnera should have been used to it by then. One final act of exploitation in a life dominated by them.

Hey, if you made it this far and didn’t hate it, you should consider signing up for the Co-Main Event Patreon. There you can comment on these posts, argue with other people about them, even call us names or whatever. You also help support the CME and keep the discourse free and unfuckingfettered.